Vocatus aut non vocatus, Deis aderit. Summoned or not, God will be heard. Inscription from Carl Jung’s grave.

Nicholas was cremated on Friday 3 December 2004 at Islington Crematorium. There was a wake afterwards at Stephen Taylor’s home in Hampstead.

Eulogy

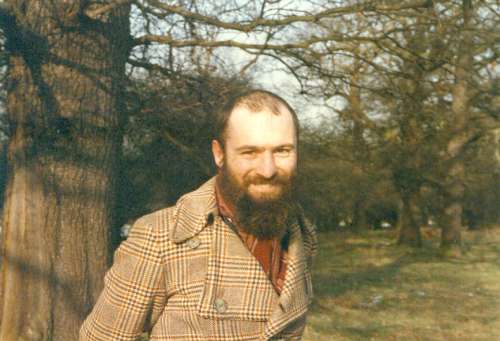

Nicholas was born in 1950 in NSW into the Battye family, respected and well-to-do colonial stock: an ancestor in the colonial forces had faced the rebellion at Forbes. His birth offered him a life of respectable comforts. He chose something else.

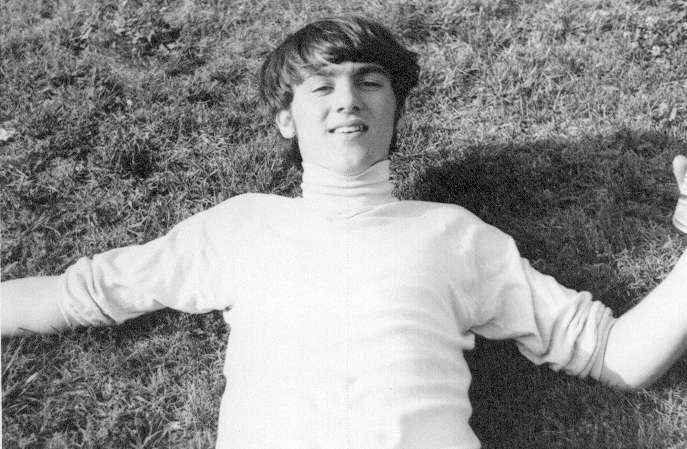

Picnic, May 1968

He was smart, he was a maverick. At 17, he was an exchange scholar, spending his last year before university in a high school in Richmond, Virginia. His classmate Rick Williamson wrote to us:

He was all about flair, fun, and laughter, and with his Australian accent he was immediately popular as soon as a word came forth from his lips. Everyone here figured he was British, and instantly fell in love with him. He was a ‘chick (girl) magnet,’ and it was not unusual for him to have several dates each weekend. He cast a large shadow of goodwill, and I was glad to be a part of the phrase, Nick and Rick.

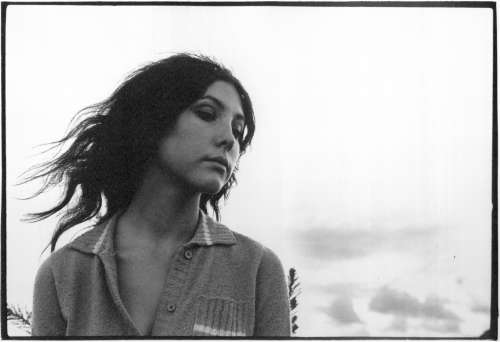

Julie Clarke

Back in Australia Nicholas was an artist and a poet, published in serious journals. It was while giving a public reading that he met Julie Clarke, then aged sixteen. Their affair finished within a year, but Nicholas carried his unrequited love for her to the grave, the first great disappointment of his adult life.

A mentor advised him to find a deserted beach until his head cleared. Characteristically, he thought London would do, and took ship before his 21st birthday.

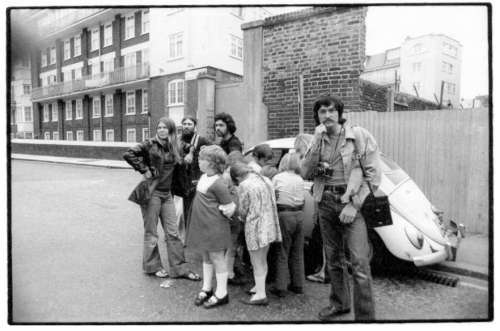

Carole, Nova, Harleigh & Sage Cole in the Hamptons, 1975

In England in the early 1970s he lived with Carole Cole and her sons Harleigh and Sage, who remember him from those and, still in later years, living without him, as their enduring and reliable father figure. Sage and Harleigh are the closest Nicholas came to having children of his own, and they remember him that way.

Exit Photography in East London

He worked as a photographer with Chris Steele-Perkins and Paul Trevor as the Exit Photography Group, documenting poverty in Britain. Their work was exhibited around the country and also published as Survival Programmes in Britain’s Inner Cities and in Down Wapping. Some of it is in the keeping of the National Portrait Gallery in London. Developing a characteristic style, Nicholas broke with his colleagues, disappointed, and abandoned his photographic career.

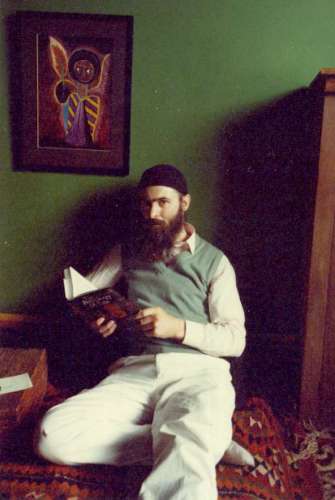

At Zen residential sesshin, late 1970s

I never asked him how he found Zen Buddhism, but that was how I found him in the mid 70s, when we both trained under Irmgard Schloegl at the Buddhist Society. I struggled with the requirement to sit in meditation for an hour a day; Nicholas put in four. He was my elder, wiser brother. The group sat during the week soon after I finished work; so a small group of us would decamp afterwards unfed to a cheap Italian restaurant in the Vauxhall Bridge Road, improbably called the New Maple Grill. I didn’t see it at the time, but Nicholas’ encouragement and friendship and acceptance of my feeble efforts enabled me to pursue the training despite my fear of groups.

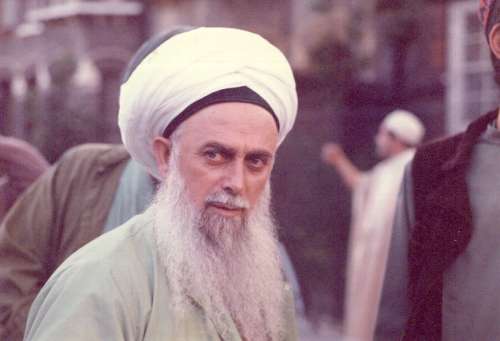

Sheikh Nazim

Some six or seven years into the Zen training, Nicholas had visions and encounters that prompted him to look for another teacher, and eventually he left the Zen group and began to study as a Sufi at Irina Tweedie’s, from where he went on to meet Sheikh Nazim.

He spent some years around the sheikh and London mosques, learning and teaching. I understand he was viewed by some as the sheikh’s right-hand man. But this too ended in disappointment, as his studies seemed to lead to no way to support himself in England. Nicholas looked again for a way to teach that would also allow him to eat.

Self portrait, 1970s

He found it in the work and legacy of Carl Jung. In 1990, having completed his own analysis, and with a growing practice of his own already, he started his training as an analytical pyschotherapist under the supervision of the professional association IGAP. Only a year later, a malicious accusation of sexual abuse was made by a former patient and aired by a journalist. Nicholas found himself ostracised, unable to complete his training, and unable to secure an explanation or a hearing. It was the last and greatest of his disappointments. Without referrals, his practice and income started slowly to dwindle.

For some years he sought without success to call IGAP to account. Ten years ago he felt he had exhausted his resources, financial and moral. He had started three careers from scratch, supporting himself with ill-paid work through long years of study. He could not in middle age imagine summoning the energy to start a fourth. He could see ahead nothing but the remorseless decay of his income and health.

This year something seemed to shift in him. I congratulated him on emerging from a 13-year sulk, a sally which he greeted with a characteristic grin. He confided that he had begun to experience visions and improbable encounters with strangers. He found and frequented “The Flying Scotsman”, a Kings Cross bar where, he said, the dancers knew more than some Zen masters.

In retrospect, it seems more like a loosening of his bonds. His always laconic diary entries trailed to a stop in April.

Then in June he fell in love with a woman half his age. His diary entries resumed for the week or two he thought he might win her, then again fell into silence.

I had earlier accused him of conniving in his own ruin. It wasn’t so. Even this summer, penurious, in ill health and shabby clothes, he could still draw an interesting woman, and allow his heart to leap to new possibilities. His despair was real, but not willed.

He had been telling his friends for some time he was tired of his life. Until the end I was one of those who stood for him pulling out of it, out of some dark night of the soul, from which he would emerge a new butterfly. Typically, Nicholas did not try to disabuse me; but he offered many hints of what was coming, which I largely ignored.

“Der Toteninsel” by Arnold Böcklin

Mark Woods has shared on the website that in his last weeks Nicholas spoke calmly and peacefully of his impending release, which he appeared to welcome. Everything in his flat after his death supports that conclusion. It seems Mark was listening to him more carefully than I was.

There were two great threads to Nicholas’ life: his spiritual quest and his search for personal happiness. His spiritual quest was driven by his idealism, his search for happiness thwarted by it.

He related always to the very best in people. He was always, always there for me, endlessly patient and good-tempered. He came to say that neither common sense nor common decency are common among humans; perhaps he was the last to discover this.

As his idealism fuelled and guided his spiritual quest, so it misled him in the commerce of money and reputation. I’m reminded of the TV series Black Books:

— What kind of world is it, asks one character, where you can’t leave your front door open without getting burgled?

— This one, Gandalf! retorts his employer.

If I’m making a lot of his disappointments, it’s because they stopped him from doing more – and how much more he could have done! For some of us it’s tempting to see this as tragedy, and his inability to free himself from his disappointments a spiritual lesson he never learned. Well it’s always easier to see other people’s lessons.

A few of us are born with physical defects like withered limbs; but all of us leave childhood with wounds that stop us growing straight and tall. A bad leg can’t be transcended; you just have to do the best you can. Psychic wounds can be transcended, and Nicholas had set himself on that path. If he didn’t reach its end, consider this: there are soldiers who fall dead or maimed in battle, having spent everything they have to give. Others are carried off ‘shell shocked’, untouched but unable to fight on. Still alive, they too have nonetheless spent what they had to give.

So consider what Nicholas achieved despite his difficulties. Unable to flourish in groups, he had with individuals the ability to make a lasting bond within the shortest of moments. He reached in and touched us in ways we will never forget. In his most difficult times, his eyes still reached in with his endless patience, endless compassion. Nicholas was always, always there for us. While we remember his compassion, we have it still.

When you were born you were crying and everybody else was smiling. Life is not very complicated. Success just looks like this: when you die, you’re smiling and everyone else is crying.

Well done, Nick.

Stephen Taylor

Tribute: Nicholas as healer

I met Nicholas 14 years ago. He began as my therapist and gradually he become my friend – my closest friend, my teacher, my mentor and spiritual guide – and I realise now he was that to so many of you too.

Nicholas therapped better than anyone else in the field, and he did so much more for his clients – because he cared so much more. Nicholas’s grasp of theory gave him the ability to position each client’s problems within the realm of psychoanalytic possibilities, and use the approaches which would best help that client. Unlike many lesser therapists, Nicholas did not impose any one school’s interpretations – regardless of whether they fit. And Nicholas did not over-interpret people’s actions that were a result of their circumstances.

Indeed, no-one knew better than Nicholas of the hardships and injustice this mean world can throw at you. Somehow that didn’t harden him. Instead Nicholas empathised – he saw beauty and sincerity in any guise.

I was troubled by the deterioration in Nicholas’s physical health, but he knew the limits of western medicine – that it would not cure, it could only plaster over his wounds and send him back into the battle field. Nicholas did not want that. He was into cures and healing. And he healed with his heart and soul – without concern for artificial boundaries. Nicholas’s therapy hour was not 50 minutes, but 60 – and some. And he gave what the client needed, be it time to sit, space to cry, ways to negotiate, guidance on meditation, or tarot readings.

Anyone who has been in conversation with Nicholas would have noticed that disarming habit he would have of looking into, or was it through, your eyes – to see what might be really going on for you. So while I was ranting or rationalising, bobbing about on the surface of my lake of distress, Nicholas was searching underwater, through the murkiness to find a way to unblock the dams. By the end of a day’s healing, Nicholas would be exhausted. And his clients would be lighter. On the way from Nicholas, I would notice that the shops I passed going to his place would always change their displays in that hour. Some months later I realised that what had changed was that on the way there I was looking down at the floor and returning my head was held high.

On hearing once, that Nicholas was helping out one of his nastier neighbours, I said, You know what he’s like, Nicholas, why are you helping him? His answer was, Because I can.

Yet, it was Nicholas’s compassion, his integrity, his scholarship, his wisdom that some couldn’t bear. Their own shortcomings come into sharp focus in the light of Nicholas.

“Over the town”, by Marc Chagall

How could a lily hide its upright stem, its height, its perfume? The bindweeds could not but see it, and they chose to stifle and strangle it, so it had nowhere to flower. And how many times could a lily put out roots and emerge in another place? While Nicholas was grateful for the support of his friends, he knew they could not provide him with the context in which he could share his knowledge and insight with the world.

The world is a greyer place now. At dusk our vision turns from colour to black and white. We can but hold tight to the memory of the vibrant colours that Nicholas brought into our lives. You were always there for us ,Nicholas – Look back into the darkness from your colourful new home and help heal this – the most painful wound of all.

Sangeeta Patel

Music: “The Healing Game” sung by John Lee Hooker & Van Morrison, from Don’t Look Back

Tribute: Nicholas as teacher

I first met Nicholas in 1988 shortly before he became one of the first students of the MA in Psychoanalytic Studies in the Humanities at the University of Kent at Canterbury. He was the best student of his year. I was later his PhD research supervisor. During this period I attended many of his lectures on psychoanalysis to postgraduate and undergraduate students at the University of Kent. More recently he delivered courses at the University on Islam in the Modern World and Sufism which were highly innovative, challenging and transformative for the best of Nicholas’ students.

I also knew Nicholas as a scholar of Sufism, Jung and psychoanalysis. Although most of his scholarship was never published, his article “Khidr in the Opus of Jung: The Teaching of Surrender” in Joel Ryce-Menuhin’s 1994 Routledge edited collection of essays (which Nicholas helped Joel to edit), Jung and the Monotheisms was identified by one reviewer as the most original contribution to the collection.

I remember his selfless love of, and tireless service to, scholarship and teaching driven by standards very little in evidence in British universities today and his bringing together of his extraordinary immediate spiritual experience with his outstanding erudition. Nicholas had the ability so often to surprise me with his first-hand accounts of religious experience and his ability to bring his scholarship to life. Like a magician, he frequently pulled rabbits out of hats and knocked me sideways, but he always ensured he was there to help me regain my balance. The distinction between stale or dead knowledge and living wisdom was instinctual in Nicholas’ scholarly life.

Nicholas was one of my closest friends since 1988, when we met at a dinner party in Mark Woods’ home. The personal chemistry between us was instant, and an energetic bond quickly developed between us that persisted throughout our 16-year friendship. I remember Nicholas’ love, loyalty and support in the good times and the bad. He always had time for me, and was always there to guide me through difficult times in my life. He understood what real friendship meant and knew how to honour it. I remember his ability to understand the complexity of any situation and to draw on all aspects of his very wide experience from the most spiritual to the most instinctual. One of Nicholas’ most striking abilities was to be able to read the souls of those he came into contact with. This intuitive faculty was immediate and the most natural thing in the world for him.

One of my most recent and treasured memories of Nicholas were our 3-4 hour dinners once a month in a Mexican restaurant in Canterbury. These were real roller-coaster journeys, ranging from the books we had read, to the political situation, to gossip (plenty of that), to matters of the heart and spiritual experience and understanding.

For Nicholas, no area of human experience was out of bounds. Indeed his love of beauty and sensuality always balanced his spirituality. I remember most about these meals the intimacy, trust, laughter (I have rarely howled with laughter the way I have with Nicholas) and his brooding and yet loving presence. It was Nicholas’ presence I loved most of all, to be physically with him, in speech and in silence. He was a real human being, a great soul. He leaves a gaping hole in my life.

Leon Schlamm

“A quiet resting”

On his mother’s death in 2000, Nicholas sent his brother Chris this extract from a play by the Elizabethan dramatist John Fletcher:

Philaster:

Oh but thou dost not know what ’tis to die.

Bellario:

Yes, I do know, my lord:

’Tis less than to be born; a lasting sleep,

A quiet resting from all jealousy;

A thing we all pursue. I know besides,

It is but giving over of a game

That must be lost.

Celia Cionnagh sings “Come Back To Me”

Come back to me with all your heart

Don’t let fear keep us apart.

Trees do bend,

’Though straight and tall;

So must we to others’ call.

Long have I waited for your coming home to me

And living deeply our new life

The wilderness will lead you

To your heart where I will speak.

Integrity and justice

With tenderness you shall know.

You shall sleep secure with peace;

Faithfulness will be your joy.

from the Book of the Prophet Hosea

Who Says Words With My Mouth

All day I think about it, then at night I say it.

Where did I come from, and what am I supposed to be doing?

I have no idea.

My soul is from elsewhere, I’m sure of that,

and I intend to end up there.

This drunkenness began in some other tavern.

When I get back around to that place,

I’ll be completely sober. Meanwhile,

I’m like a bird from another continent, sitting in this aviary.

The day is coming when I fly off,

but who is now in my ear, who hears my voice?

Who says words with my mouth?

Who looks with my eyes? What is the soul?

I cannot stop asking.

If I could taste one sip of an answer,

I could break out of this prison for drunks.

I didn’t come here of my own accord,

and I can’t leave that way.

Let whoever brought me here take me back.

Jelaluddin Rumi

from Open Secret: Versions of Rumi by John Moyne & Coleman Barks

“Death is nothing at all”

Death is nothing at all. I have only slipped away into the next room. I am I, and you are you. Whatever we were to each other, that we still are. Call me by my old familiar name, speak to me in the easy way which you always used. Put no difference in your tone, wear no forced air of solemnity or sorrow. Laugh as we always laughed at the little jokes we enjoyed together. Let my name be ever the household word that it always was, let it be spoken without affect, without a trace of a shadow on it. Life means all that it ever meant. It is the same as it ever was; here is unbroken continuity. Why should I be out of mind because I am out of sight? I am waiting for you, for an interval, somewhere very near, just around the corner. All is well.

Henry Scott Holland, 1847-1918

Canon of St Paul’s Cathedral

Supplication

“Angel with the Burning Sword”,

by Nicholas Battye

O God! Forgive him. Have mercy upon him. Give him peace and absolve him. Receive him honourably, and make his grave spacious. Wash him with water, snow and hail. Cleanse him from faults as though Thou didst cleanse a white garment from impurity. Requite him with an abode goodlier than his abode, with a household goodlier than his household, and with a mate goodlier than his mate. Cause him to enter the garden, and protect him from the torment of the grave, and the torment of the fire. Amen.

Traditional Muslim prayer

Music: “Amazing Grace” sung by Mahalia Jackson, from A Portrait of Mahalia Jackson

Music: “Over The Rainbow/Wonderful World” sung by Israel Kamakawiwo’ole, from Facing Future